ABJ: An Artistic Dialogue Between the Diaspora and its African Roots

How Art Bridges Francophone and Anglophone Africa

Dear curious minds, I should have posted a paywalled story for the Black Europeans You Should Know series, but in between health issues and falling into a rabbit hole of information (in German, that I understand a little bit!) about the people I want to write about, I still need time to polish that story, so pardon me. Nonetheless, I have my last story written for the fourth edition of Naïfs Magazine for you, so here it is! I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Emeka Ogboh, a multidisciplinary Nigerian artist based in Berlin, is known for his installations that engage all the senses. Invited to Abidjan at the SOMETHING Art Space created by artistic director Anna-Alix Koffi, the artist recreated the bustling markets of Abidjan with videos, sound, and objects. Paradoxically, I conversed not with him but with Zhedy Léna Nuentsa, a creative strategist and thus a key figure behind Emeka Ogboh's exhibition titled ABJ. This conversation between two children of the Cameroonian diaspora did not only focus on Zhedy's role and the behind-the-scenes aspects of a digital exhibition, but it also provided an opportunity for each of us to discuss our relationship with Cameroon through art and the connection between former colonizing countries and their former colonies through the lens of artistic projects. It was, therefore, a discussion where art was central. It also allowed us to talk about identity, the remnants of colonization, and our pride in seeing African diasporas and Africans learning to know each other through art.

You work for the Goethe-Institut. Could you discuss your role in Emeka’s exhibition within this institution?

I am a freelance creative strategist, which encompasses many things and nothing at the same time. The Goethe-Institut hired me to work on ABJ, the exhibition of Nigerian artist Emeka Ogboh.

I coordinated with the international press in this particular exhibition and brought in influential individuals. At that time, in Abidjan, there were a lot of opinion influencers, so my role was to bring them to the exhibition to talk about it and to contact media outlets around the world to discuss the exhibition and what was happening in Abidjan. So, it was a coordination job in press relations. But then, with exhibitions like this and when it's a small team, you end up doing production, photography, a bit of everything. But that's also what I like about my job.

But it's no coincidence that I’m in this position: I worked on the opening of SOMETHING Art Space in Abidjan.

Since you participated in the opening of SOMETHING Art Space, could you talk about its beginnings?

I should mention that I live in Paris, so we worked for months on the programming while the space was still under construction. Those were really challenging months. Since SOMETHING Art Space is also a non-profit venue, the issue of funding is always present: how and where do we find it? Where do we allocate it? What do we have to leave out? How do we get people to come, etc? For me, it was an extremely exciting and challenging experience, as it involved creating a place that, to my knowledge and I did my research, had never been seen before in West Africa, if not the entire continent, that is entirely dedicated to digital art. The first opening took place in September 2021, and it was very interesting because it was the exhibition The Powder of My Hands, which was dedicated to African women. It was loaned to us by the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. For the occasion, we brought in the curator of this exhibition, as well as some of the artists, and it was truly a remarkable moment. I hope that in the future, reviews will reflect on this pioneering moment, showcasing the potential of art on the African continent.

It seems pioneering in the sense that we are talking about a gallery with a digital focus, but also because, often, when the subject of repatriating African art objects to the continent comes up, the common objection is that it’s not possible because they don’t have the tools or the venues. Now, the fact that this space could host an exhibition in Paris shows that it is indeed possible when the conditions are right.

It's completely possible, and in fact, it's quite unique. What you're reminding me is that we mustn't forget that the African population is the youngest in the world, and it will remain so for a long time. The first technological device the majority have is the smartphone because it's the most accessible. The smartphone allows them to have an internet connection and to take photos. That's how the new artistic wave is going to emerge. Ultimately, it's much easier to take out your phone, shoot footage, and create something with your phone than paint. It's really strange to say this, but being a painter is expensive. You have to buy the gouaches, the brushes, and the canvases, whereas to make a video piece, all you need is the smartphone that everyone has daily. That's also why SOMETHING Art Space is important and will be in the years to come, and I hope there will be other galleries of similar scale created.

What you're saying is really interesting because it's true; we don't often think about it. For my first article for Naïfs, I interviewed Adora Mba, a Nigerian and Ghanaian gallerist, and she explained that many African artists were held back due to lack of funds, for instance, to access training programs.

Of course. That's also why many of them are self-taught, and there's a lot of upcycling. They use materials they have at hand to create instinctively. I don't even think there's a deep thought process like, "Oh, I don't have paint, so what do I do?" It's more like, "Okay, what do I have around me? Let’s create with that. »

Back to SOMETHING Art Space and what you mentioned about it being one of the first spaces of its kind in Africa, West Africa, and, more specifically, French-speaking Africa. I specify all of this because I find that there's little discussion about French-speaking African countries in the art market. However, Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa are the ones in the spotlight.

Emeka is Nigerian, and I don't think one would necessarily expect to see an English-speaking African artist in a francophone African space.

It's even more complex. Emeka is a Nigerian artist living in Berlin, so he isn't even francophone. One might have thought that living in Europe, he would be in a francophone country or Canada, for example, but no, he isn't francophone at all. But Emeka's choice is connected to Anna-Alix. For over 15 years now, she has been bringing all these artists to the continent, encouraging them to come to Abidjan, and she's not the only one. This is from my outsider's perspective. I'm not Ivorian. I should specify that I'm of Cameroonian origin, Parisian and French.

Oh, that's funny, I'm Cameroonian too.

It's weird, but whenever I talk to people and they introduce me to others to work in this world of art and culture, I only end up with Cameroonians. It's crazy. Something is going on in Cameroon. In many initiatives, if you look closely, there's always a Cameroonian or someone from the Cameroonian diaspora involved. The craziest example, I don't know if you remember that meeting between Justin Bieber and Emmanuel Macron, where he went to the Elysée Palace, well, it's a Cameroonian living in L.A. who's behind that.

When I think about it, there is Cameroonian art curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung.

Yes, he was in Abidjan for the opening.

I met him in Berlin at an event at SAVVY Contemporary, the art centre and laboratory he founded. In addition to this organization, he is also the director of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. A Cameroonian at the head of a museum in Germany... There is something about the Cameroonian diaspora and Cameroon. I know things are happening in the art world, but we don't hear about it due to the country's political climate. But let's return to Côte d'Ivoire.

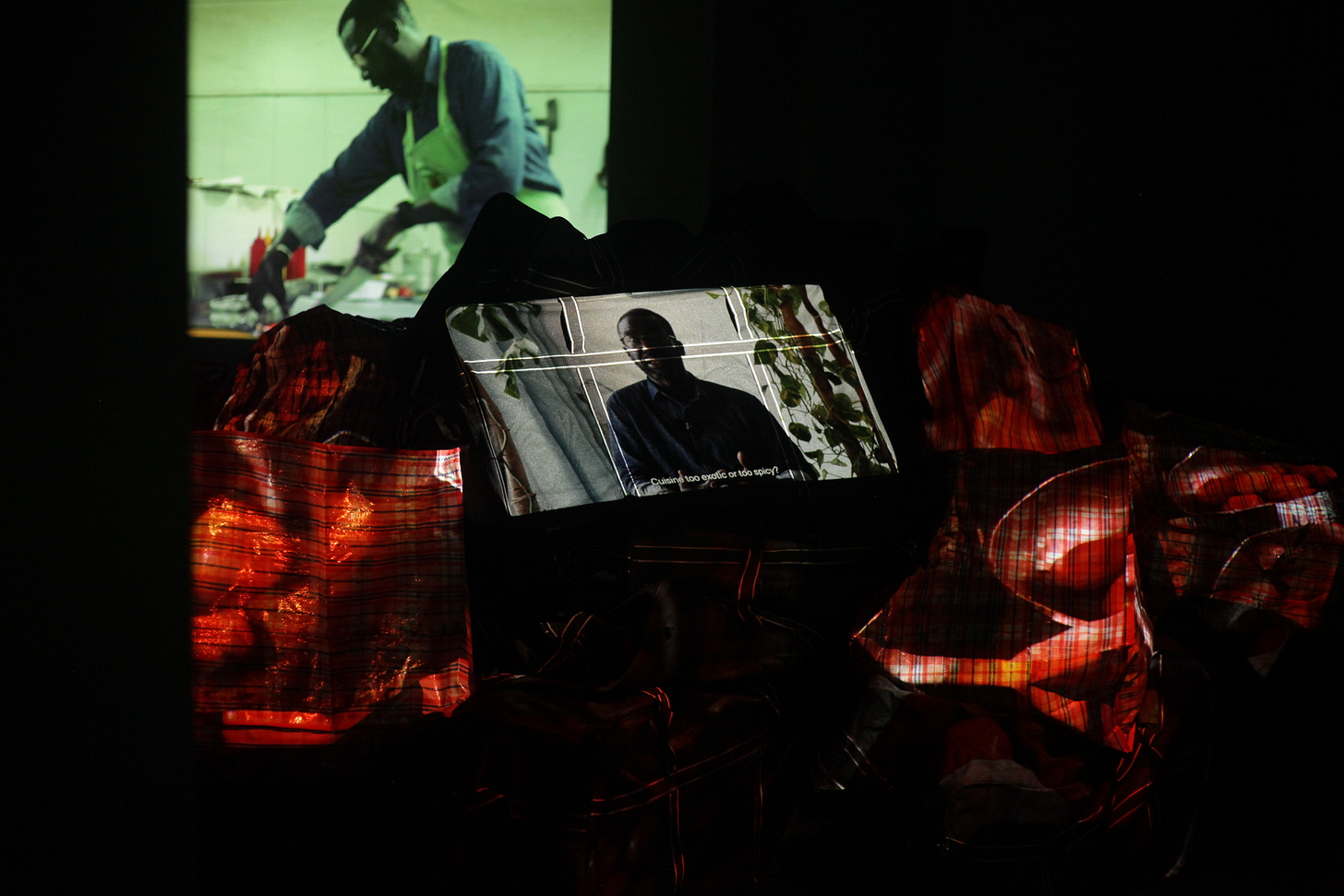

I met Emeka Ogboh at Documenta 14 in Athens, one of the major art events in the Western world. Anna-Alix had invited him to Abidjan for the first time to introduce him to the city and this francophone African country. She adopts this approach with several African artists from the continent and the diaspora because Abidjan is not necessarily part of their travel plans. He came back a second time to capture the sounds and meet people. I should mention that ABJ is an immersive experience, so there is sound and imagery. You know that in Africa, you don't just walk into a market like that. And even without going too far, you don't arrive at Château-Rouge [editor’s note: it is an area of Paris known for its diversity with shops selling wax fabrics and products from all over the world. It is also known for its braiding salons] and start filming people as if it were your home. There is an adaptation period; you must build trust with the people. And even though the exhibition is still open, Emeka really wants to create a lasting relationship with this city and bring his fellow Nigerians, artists or not, to Abidjan. He wants to develop other projects around local beer music and is thinking about an album with local artists. So, it is an exhibition that aims to continue and perhaps go to Lagos. The idea is for it to take place in both cities.

But it’s incredible because what you’re saying also shows that we don’t know each other in Africa.

Exactly. We don’t know each other, and especially with the language barrier, it’s as if they are discovering another Africa. Geographically, Africa is not Europe. Every time these initiatives happen, I find it quite incredible that the artists are discovering a new world. We talk so much about going to Europe that they are almost more familiar with Europe than with other African countries. At the time, I was working on another project simultaneously, and it felt like the African Cup of Nations. Many people from the diaspora arrived on the continent or in Abidjan, and ultimately, the differences weren't the only ones highlighted. For example, I shared an apartment with two Nigerian collaborators during my stay, and the similarities struck them. They were so happy to realize, “Actually, Ivorians, people from Abidjan, and people from Lagos are the same.” As a Cameroonian, I have seen, since I was very young, the similarities between Ivorians and Cameroonians. I know that culturally, there are things that are not so different, perhaps also because we are francophone. So, it was truly a joy for these Nigerians I was with daily to observe these similarities despite the language barrier. Their takeaway was that they needed to learn French and travel more in West Africa. That was the conclusion for most people. I even met Haitians and Rwandans who came for the exhibition and AFCOM. For many, it was their first return to the continent, so it was a truly special moment, that Afro-diasporic summer in Abidjan.

I found it fascinating that the exhibition was so focused on Abidjan and that the city was seen through the eyes of a Nigerian artist based in Berlin. Why the choice of the market?

Two things. Emeka works a lot on immigration, the experience of being far from home, and the market in Africa in general, and this one in Adjamé in Abidjan is no exception. It's often a place that crystallizes many immigrants. Since time immemorial, the market has brought together traders and passersby, who settle down or return home. Since the market is a theme inherent to all of his works, it was an obvious choice.

The photos with the "Ghana Must Go" bags are very striking. Not long ago, I read an article about these bags called Ghana Must Go in the Articles Of Interest newsletter written by podcaster Avery Trufelman, and it was super interesting to know that they take on a different name in each country. For example, in Kenya, they are called "Nigeria bags," and in Zimbabwe, "Botswana Bags." So, in each country, they take on the name of the neighbouring African immigrant.

That's funny. Do you know what they're called in Cameroon?

No, I have no idea, and it's not for lack of trying. But it was really interesting to learn why these bags are called "Ghana Must Go" in Nigeria: overnight, after the collapse of the oil market in 1982, many Ghanaian immigrants were expelled, and these bags became emblematic of their abrupt departure. So, when I saw these bags, I immediately thought of the themes of immigration and the market, as they are also characteristic of this place.

I call them Tati bags (a French brand known for selling inexpensive textile goods), but again, they are always associated with immigrants because Tati, in France at least, was one of the major symbols of the diaspora, not necessarily African. I believe that in Asian communities as well, before returning to their home countries, there was this passage through Tati, where they would buy in bulk before leaving.

How did you set up an exhibition of this scale? Because I'm not necessarily used to visiting spaces where many things are digital.

I don't want to resort to miserabilism, but there's an electricity issue in Africa. You never know with electricity because you can have a blackout. We might have had a five-minute outage while I was there, and I stayed for a month. But there's this fear, at least I had this fear of, "Will the screens hold up?" "Will we not have a power outage?" because we do not control this electricity problem. In any case, building an exhibition of this type requires a lot of people and techniques. The scenography was done by Clémence Farrell, a woman who does the biggest scenographies in Paris. The last big exhibition she did was for Johnny Hallyday. For the video, Emeka was accompanied by a young French-Ivorian woman who followed him in the markets, took the photos, and provided translation. After that, it's like any other exhibition. All these hands are working on the scenography and the plans in advance. We set it up, see how it works, and hope the electricity holds up.

What you say about electricity is interesting because it's a challenge.

We created an entirely digital space in a place where we can never be sure that there will be electricity, which means there's a risk that people won't be able to enjoy the exhibition in case of a power outage. This isn't the first thing that comes to mind in Europe or the West when setting up an exhibition. There will clearly be other problems, but not those related to electricity. When we talk about exhibitions in Europe and the West, we immediately get to the heart of the matter: the artist, their inspirations, and so on. But we don't really talk about the logistics. It's as if it's not a subject. That's why earlier, for example, when we were talking about the repatriation of artworks to Africa, the infrastructure issue and the preservation of artworks with the heat and the climate, in general, bothered me.

But these artworks in Africa were there before.

Exactly. These are artworks that were there before. Sometimes, I can even be a bit extreme on the subject: if I want, I can leave an art object in the basement to rot. And that will be it.

I see your reasoning. I was raised by a white Frenchman who worked in Africa for almost 30 years. During his travels, he brought back many masks and statuettes. And there are things that we can't bring into the house anymore. Clearly, there are things in the garage that have gathered dust and have even rotted. But that's also the life of a piece of art, an object. Whether we like it or not, there are things that we won't be able to preserve. In the West, the conception of "African art" completely differs from what we have in Africa. You won't find masks or statuettes in people's homes.

Yes, they are often visual objects with a highly spiritual significance used for ritual practices or everyday objects. So, people either fear them because they are not supposed to handle spiritual objects or don't necessarily see their value. It's a different approach. There’s another point I forgot to mention: the responsiveness and ease of working with the Goethe-Institut. I didn’t handle the negotiations myself, but having worked with the Institut français and the Goethe-Institut, which have the same mission for their respective countries, my experiences with the Goethe-Institut, especially for this exhibition, have been much smoother. We talk about differences between countries and cultures, the relationship with colonization, etc. As a Cameroonian, I know this very well [editor's note: Cameroon was discovered by Portugal but was first colonized by Germany until it lost authority to France and the United Kingdom at the end of World War I]. However, the relationship with the Goethe-Institut is different. The freedom of expression they allow, the people they hire, the funds they provide, etc. The approach is completely different from that of a French institute. I specify because I haven't worked with all the French institutes in the world, but at least those in Dakar and Abidjan. It has been much easier and smoother to work with the Goethe-Institut.

From the outside, I observe a bit of "white saviorism" in French institutions. I know that the Goethe-Institut has many initiatives in Africa, but the individuals who present or organize a project are not necessarily German, for example.

In the case of ABJ, that's actually the situation. Rainer Hauswirth, the director of the Goethe-Institut, who worked directly with us on the exhibition, is German and has been living in Abidjan for over ten years. And the rest of his team, honestly, without exaggeration, is 95% African. Even within the team, I'm talking about the permanently employed people; among them were Nigerians, Cameroonians, etc.

It's a different approach. It goes back to the German colonization system, which differed from the French one. The German colonization model is a bit like the English one: colonial administrators had to know the country and the culture of the place they were going to. They studied it. Whereas with France, colonial administrators were not trained on the peoples and colonies where they were going. And it's not just a question of expertise but also interest.

There's something with France where you have to adapt to your colonizer. It may sound paradoxical, but it needs to be said. We won't applaud colonization, but there are really different methods.

These are different approaches. I'm not saying one is better; however, these approaches have also shaped the mentalities of certain countries.

Of course. And it has consequences on collaboration today, on respect. After all, the Germans have a completely different approach because they had the Holocaust in the meantime, so they have a repentant approach that the French don't have.

In France, we don't have the same approach precisely because we are still imperialist.

Get your copy of Naïfs Magazine here

I loved this!