Hugues Lawson-Body Or The Art Of Writing With Light Pt.2

Giving a voice to hyper-visible yet invisible Parisians

Thank you for reading Le Journal Curioso! This newsletter is accessible to everyone, and as much as it is a labour of love, it is also a literal labour of research, time, and writing for you, my dear Curious Minds. Consider upgrading to a monthly subscription at 6€ or a yearly one at 48€. Your support means the world to me!

Before plunging into the thick of this interview, I wanted to welcome and thank the newcomers. Because I know many of you read Le Journal Curioso via email, I highly recommend perusing the first instalment of today’s piece - which I linked below - to get to know Parisian photographer and director Hugues Lawson-Body’s background and story. It will help you contextualise today’s story.

In the second instalment of my interview with the photographer and director, Hugues Lawson-Body, we focused on:

Introducing his YouTube series, the Barber Show

His experience as a Black man at a barber shop

His view on diversity

His last documentary about Bike Life, a sport that is quickly becoming the new skate

Hugues has explored video for a long time; it began long before the digital revolution, and he has been visiting movie and video sets since the beginning of his career. As a true enthusiast, he first discovered the art of animated images with a Sony camera to shoot a documentary in Jamaica that will, unfortunately, never be produced.

The digital revolution - combining photography and videography - finally arrived, yet Hugues’ first experience did not turn out to be exciting until the Barber Show. “In 2005, I was looking for a barber who would not be afraid of the camera, and some friends told me about this guy named Babs. I eventually landed in his barber shop, which was a little off Strasbourg Saint-Denis. And there, I met this exceptional character. Babs is very relaxed; to describe him briefly, he has SWAG. I admired him and his buddies. He became my barber, which made me realise that my last one was actually horrible. I don’t even know why I always went back to him. He was expensive, yet unkind, and he’d hurt me. In short, the whole experience was a disaster. At Bab’s place, it was the other way around, and I felt really good. I felt like I was at home, like at the therapist’s, which made me realise it was a social club. Then I thought, ‘If I come with cameras, are the guys staying their authentic selves?’ I tested my idea, and we filmed something really cool, raw, and authentic. And indeed, the guys stayed true to themselves!” he says enthusiastically.

His meeting with Babs again proves that Hugues does not see the people he shoots as subjects but as human beings with full-fledged personalities with whom he has fallen in love. As you can see, places are still fundamental to him. In his eyes, this barber shop was much more than a place where he went for a mere haircut. His experience at the barber shop echoes that of many Black women, for finding a salon where people know how to take care of afro hair with impeccable customer service and affordable prices may be a harsh quest. When you finally find one, getting your hair done becomes a moment for yourself and your well-being. Seeing Hugues discovering it through this project is all the more revealing as barber shops are not usually perceived as places of sociability when they actually play this role, just like women’s hair salons. Babs and his best friend Gaye discuss several topics with customers and onlookers in each episode. The crowd in this tiny barber shop is crazy. Some are there to get their hair and beard done, others come to kill time, while the rest are looking for gossip. Babs’ customers, friends, and acquaintances are representative of a France that is too often negatively depicted.

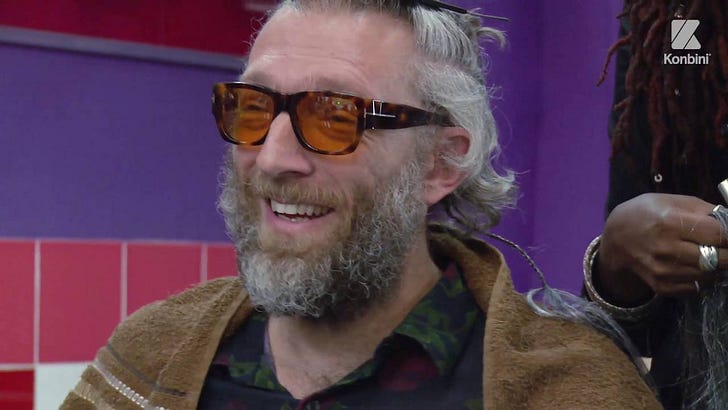

Through Hugues’attentive eyes, these people reveal themselves, far from the stereotypes mass media convey. Everyone chats fervently about various subjects, such as Jay-Z vs. Kanye West’s cultural capital, male infidelity, and the images of the World Cup, where we can see Babs among other Parisians. In one episode, they also speak of cinema as Vincent Cassel enters the barber shop. Hugues declares: “As he grew up with a father who was an actor, a brother who is a rapper and a sister who also works as an actress, his arrival didn’t seem to faze anyone. He talked about cinema while getting his hair braided. He did not seem embarrassed and spoke on an equal footing with those “invisible” Parisians, who actually are part of the city's magic.”

Below is the episode in French I mentioned earlier - pardon me non-French speakers - with Vincent Cassel. Even if you don’t understand French, I hope watching it will give you a glimpse of the experience.

This approach reinforces “the idea of showing the different voices and points of view of Black, Arab or white people living together and talking about common subjects.” Hugues wished to show France’s diversity through this series because there is no single way to be French. This vision he has had since his youngest age, and this diversity he has witnessed, pushes him into cultivating this political view despite the divide that has been plaguing the country since 2001: “You grow up with your environment, you don’t wonder who is Black or white because we are all together and we evolve together. The distinction was made clear to me after the 9/11 attacks when people started withdrawing themselves because they got tired of being constantly attacked. Ever since 2001, public authorities have failed to spread the idea that being French, no matter one’s origins, means being one and unique.”

Hugues’ vision is very different from mine, and yet we are “only” 10 years apart, but it seems that a decade is enough to change everything. I grew up in a France, where separation through social class, status, and skin colour was much more pronounced. I can not recall this sense of French living together. I don’t want to say that it may be a utopia, but the France in which Hugues grew up seems to be light years away from mine. I am way more pessimistic and sceptical regarding France and its perception of immigrant children than he seems to be. On the other hand, I appreciate that Hugues wasn’t in denial when he said: “Yes, we live in a racist, fragmented, and divided society. At 5.00 am on line 11 in the RER B, there are only Black and South Asian people, and the closer you get to La Défense, the less diversity there is, but I feel we are still diverse.”

Hugues is all in nuance, and this is what makes his work all the more precious and appreciated. Besides the Barber Show, the director displays a disarming versatility. He can jump from a documentary about the last months of the iconic concept store Colette before its final closure to another one depicting young Parisians who ride high-speed bikes on one wheel. Bike Life, the name of that sport, is the new skate of this generation of teenagers who film their prowesses and post them on TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat. By doing so, they turn themselves into movie directors and actors in their own stunts. We can feel that these young people fascinate Hugues, not only for the new codes they are creating through Bike Life and the culture that derives from it but also because they enable him to witness another revolution of the image with mobile phones that now allow us to record and edit videos instantly. Even after having lived a lifetime in Paname - one of the many monikers of Paris - this city and its youth keep entertaining Hugues, who describes himself as a portraitist and sociologist.

Original Text Emmanuelle Maréchal

Translated From French by Shaughna-Kay Todd

Contribute without strings attached to help me reach my 2024-2025 goal: a.k.a. pay for my driving license. I know not all of us can commit to supporting every writer and artist we love regularly. If you can’t commit to a monthly or annual subscription but still want to support, you can buy me a coffee below.