Can Fashion Criticism Keep Up With Fashion Weeks'Fast Pace? Part.1

How Italian Independent Fashion Magazine Rivista Studio Approaches Fashion With Its Fashion Director Silvia Schirinzi

Le Journal Curioso is a reader-supported publication. The idea behind that publication is to write about fashion from angles you won’t find in mainstream media. If you are enjoying this article, feel free to upgrade to a paid subscription.

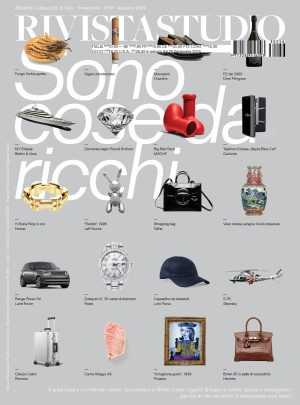

As Milan Fashion Week kicks off, today I am presenting you with a story about fashion criticism from the point of view of Silvia Schirinzi, the fashion director of the Italian independent culture and lifestyle magazine Rivista Studio. This publication is a refresher in the Italian media panorama as it thoroughly tackles topics online and in print. It gives an idea of Italian fashion, culture and pop culture from a unique point of view. The way they approach non-Italian topics is also a refresher as it is not cliché. Sorry, but not sorry to Italian journalism, but very few are of quality.

I chose to interview in my Underrated Fashion Professionals Talks Series because she works for an independent quarterly magazine, so I was curious about their approach to fashion criticism in that regard. And as Rivista Studio is not only about fashion, it was even more fascinating. That is why this conversation is in two parts. I will post the second leg of our talk on Wednesday, 28th February.

In this first part, we talked about:

Rivista Studio,

Rivista Studio’s approach to fashion

How the industry has changed in the last five years, and how it has impacted fashion criticism

Hello Silvia, can you please introduce yourself?

Sure! My name is Silvia Schrinzi. I am the Fashion Director of the Italian independent magazine Rivista Studio, which is geared toward culture in general. So Rivista Studio isn’t just about fashion; it tackles literature, cinema, and TV shows. In brief, the publication approaches topical issues from a wide perspective. As we are a printed quarterly magazine and a daily online newspaper, we are looking to — online and in print — approach topics of high interest with a broad view so that, ideally, readers can buy each edition, have time to read it and deepen their knowledge. We especially focus on the cultural aspects of topics that traditional media might cover less.

Can you expand on how Rivista Studio tackles a topic?

Yes, of course! For example, our last issue was about wealth, generally speaking. We tried to approach the whole phenomenon as it has been THE topic in the last year and a half, from the pandemic to the resurgence of Quiet Luxury, trying to understand why we are back to talking about rich people in literature, cinema, and fashion, and why we are now obsessed with them when from the 90’s to the 00’s we didn’t care about them, and how behind that imaginary there is an ideal of conservatism.

There is a return to an elegance that has always been white and occidental. Even though a specific place doesn’t define that elegance, it has specificities that link it to a unique image that we believed we had gotten past, thanks to all the world’s twists and turns, especially within the fashion industry in the last twenty years. I am thinking about how streetwear opened the conversation and turned fashion upside down, for example.

Nowadays, instead, with the pandemic, we are realising that all the conversations around fundamental topics like inclusivity and diversity have been put on the back burner. And we have gone back to this idea of dressing like rich white American and European people from the 60’s. This shift hides a reactionary impetus, as it signs the return to a beauty and luxury standard that took over fashion and that we finally thought we had overcome. So, we believed fashion had become a welcoming space for many conversations. Instead, it all has disappeared. Yes, you will see a Black or an Asian model here and there, but creatively, it is all about business and in terms of changes, we live in a period of conservatism. So this is what we are trying to do at Rivista Studio: tackle big topics and question them so we can give tools to our readers that go beyond what they read elsewhere.

How do you approach fashion at Rivista Studio?

Fashion is a big part of Rivista Studio. I work alongside Tommaso Garner, our Creative Director, and Cristiano de Maio, our Managing Director. The magazine is a little bit organised like a soviet collective. Tommaso, Cristiano, and I look after the direction, but as we aren’t a lot — we are a dozen people — it allows the publication to be the union of a collective of points of view. After Federico Sarica, the founder of Rivista Studio and the current GQ Italia Editor-In-Chief, left, we thought having a figure like an editor-in-chief didn’t reflect us.

The role of the fashion Editor-In-Chief, like that of the fashion critic, is a twentieth-century figure that is becoming a little bit obsolete. In fact, today, nobody needs a fashion critic. The success of a collection doesn’t rely on these figures that have historically defined fashion. The famous’ blue sweater scene in The Devil Wears Prada…well, all this mechanism today doesn’t work anymore because first fashion has, let’s say, opened up, yet at the same time, it has lost relevance, or better said, it has lost its capacity to dictate the rules. That is why we realised that the fashion we have been discussing has always been Eurocentric, or very occidental, and therefore exclusive.

Very important markets with huge creativity always operated in parallel. We just never told about them, so today, that deception doesn’t exist anymore. There are many other creativity centres, either in Africa or in Asia, that are very different from one another and that more and more have been focusing on themselves in the last few years since the pandemic. So the occidental market that has now become old under various aspects, especially the European one, is less and less interesting.

If we are just thinking about Accra, for example, they do a fantastic Fashion Week, and so is Lagos in Nigeria. In Asia, India is a humongous market with a sartorial tradition and a supply chain production similar to the Italian one. It is probably one of the few countries to produce in the same place from start to finish. Then there is China, whose market is facing a slowdown resulting from their drive to buy Chinese. But it isn’t unique to China; it is happening in other markets. There are plenty of African designers who cater to African customers, a clientele that occidental brands have historically not paid attention to.

I have talked to you about three markets that are very different from one another, but that exist in parallel with the other four fashion weeks, which we consider the most important: New York, London, Milan, and Paris. So with that perspective, the fashion critic is needed because there is a huge interest in fashion, especially from younger generations. This said young people don’t find something that answers their questions about fashion in classic fashion criticism, with few exceptions.

Regarding fashion criticism, I observed something quite interesting this season, especially during the first Sabato de Sarno’s show for Gucci. I noticed a gap between the Italian fashion media that seemed to protect a young Italian talent and the American and British fashion media. I don’t mention French fashion media because fashion criticism in France doesn’t exist. There is always been a gap in fashion criticism between Italy, the USA, and the UK, but I am wondering why, this season, it seemed more obvious.

Gucci is a great example. I would add to that gap you have noticed a third opinion or rather opinions. I don’t know if you have read and watched on Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok, but many people loved Sabato de Sarno’s Gucci because they perceived something more attainable in it than Alessandro Michele’s Gucci. In his seven years of tenure at Gucci, Alessandro Michele, who no one knew, started quietly before affirming himself as one of the most important fashion designers of our time. But in the end, there probably was a little fatigue, not because he isn’t a great designer, but because the fashion cycle goes so fast that it begets exhaustion. So, a customer or admirer of the brand who may not have any buying power might have felt excluded from Michele’s Gucci, which was so eccentric and full. It is no wonder, then, that people loved such a neat Gucci.

About fashion critics, I believe they were waiting for an opportunity to critique a big brand part of a conglomerate like Kering. The most cut-throughs were the Americans and the British to some extent. But in Italy, usually, apart from a few exceptions, we are more cautious when judging a first collection.

In Business Of Fashion, Tim Blanks has been very harsh, and so has Rachel Tashjian of the Washington Post, whereas The Cut’s Cathy Horyn has given him a little bit of the benefit of the doubt, which is fair, in my opinion. Surely, in Gucci’s case, there was a discrepancy between the communication anticipating the show and the actual show. Then, it didn’t help it was relocated. The litmus test will be when the collection will hit the stores, so it will be difficult. Sabato de Sarno started during a very complicated moment in the fashion industry, firstly because Gucci has a massive legacy as a brand and because of Alessandro Michele’s contribution. The economic uncertainty is another factor, as the next months are downwards, and the last economic projections are negative; the big conglomerates are in a difficult position, except Hermès, which is +16%.

The fact brands are standing the test of time with the same products and discreet communication despite the economic crisis is due to their catering to their VIC (Very Important Clients). Bottega Veneta has been having quite the success at repositioning itself, with its jeans costing 19 000 € and bags starting from 11 000 €. We are talking about an incredible price increase that happened right after the pandemic, as big luxury fashion players thought that with the return of Asian tourists in Europe and the USA, they would buy less. So they set their prices accordingly. And because of all those factors, fashion criticism has no weight.

There is surely a way to be part of the conversation around pop culture, especially on social media, for already successful brands. This was the case for Brunello Cucinelli and Loro Piana, who organically profited from the quiet luxury trend. But it doesn’t mean they didn’t do anything. They just happened to find themselves swept into that conversation because their aesthetic made a comeback, but they have always been there.

I agree with you. When I was working at MyTheresa, Brunello Cucinelli and Loro Piana were brands that brought money in without doing that much.

Exactly. And that is a paradox as brands like Gucci, Balenciaga, and Saint Laurent, who are more attached to aesthetics, fashion shows, and testimonials, struggle. So Sabato de Sarno has a hefty weight to pull, and he needs time. I believe that is the big lesson of that period: brands part of big conglomerates that need to answer to the logic of constant growth need to have the time to navigate this uncertain era to cultivate an aesthetic and a vision.

An example is Prada from 2015 to 2018, who, during the big success of Alessandro Michele at Gucci and Demna Gvasalia at Balenciaga, wasn’t doing well at all. So they invested in the Fondazione Prada, organising various cultural events. Prada is what it is today and the only independent, storied Italian fashion brand that managed to navigate this period because when they relaunched Miu Miu, they understood it would take them five years. Within conglomerates owning various brands, it is impossible to wait for five years. That is why I believe that many fashion critics, even the most influential of our generation, sometimes tend to judge a single collection while overlooking today’s fashion landscape that now involves such a prevalent entrance of the finance world. So we expect a collection to do miracles.

From that point of view, Alessandro Michele and Demna Gvsasalia made a miracle, especially as fashion five years ago wasn’t what it is today. But let’s not forget that Virgil Abloh also contributed to revolutionise fashion.

Agreed. I also wanted to add that when I think about the generation before with people like Alexander McQueen, it wasn’t money that motivated them. With LVMH and Kering, whose focus on fashion began fifteen to thirty years ago, they completely flipped our conception of fashion and how fashion criticism is made. I think that a fashion critic who used to write only about clothing now has to know about the economy, finance, and what is happening in the world to be able to write how all the dynamics affect a collection, a brand, the sales, etc. And I don’t think they are always well-informed.

Yes, now the job of a fashion critic requires a different training. There are so many factors to take into account, so that is why I don’t believe in harsh criticism. Surely, on social media, you will get eyeballs because it feeds on polarisation; writing a collection was awful. But in reality, it is more complex than that.

Fashion critics, when they do their job well, don’t express themselves too much because they know a collection needs time. This approach is typical of publications that do quarterly or yearly editions. It is there that you can find more in-depth reflections. I really love Dean Kissick, who is, in reality, an art critic who was an editor at Spike Art Magazine. There, he had a column where he reviewed shows. He usually writes about contemporary art. His reviews of Balenciaga's shows, when they had all the art installations, were insightful because they expanded on the relationship brands have with contemporary art. He did the same with the culture of celebrities inside fashion brands. Often, this type of reflection takes time, and it is no wonder they are born on platforms that are not Vogue Runway or similar publications. Such reflections not only need time but also need people to absorb them. And it is not during fashion week when brands, who, by the way, perfectly master their storytelling now, bombard us with content that it can be done.

And that’s it for the first part of that interview! But before leaving you, I’d like to ask you a couple of questions:

What quarterly or yearly magazine do you read?

What is your experience reading them?

Love this interview and it's so true that critics can no longer simply critique the designs from a cultural/design aspect, but they must also consider the economics and the ethics of production, given that fashion is now an industry. I think Robin Givhan at Washington Post is especially skilled at discussing the sociopolitical aspect of fashion while still focused on critiquing the collections; perhaps we need more like her! I miss Sally Singer's take on the collections, which were published in Vogue US months after the collections had been shown; they felt deeper, less reactionary and better contextualised.

I'm excited for part 2! I think it's interesting her note about how fashion criticism needs time... I do do enjoy a reading a critic's first impressions, whether harsh or not (I do really enjoy rachel's washington post pieces) but I think both amy's interview and this one does make me question what value a fashion critic brings to the broader fashion landscape out side of the views/clicks form a "harsh" review.