This Past Files was previously published in Italian on

, the currently paused newsletter by ex-Vogue Italia Senior Fashion News and now Gucci’s Head of Communication, . In her Pitch Perfect column, she allowed writers to write about a topic of their choice. I picked the Parisian/French woman stereotype not because it is an obsession but instead because I think it is necessary to have it etched that this thick-skinned cliché is damaging and contributing to perpetuating a false image of France. Despite Emmanuel Macron’s disillusions that France is a political and diplomatic powerhouse worldwide, the country still holds significant soft power through the culture of francophonie AND luxury. The Parisian/French woman stereotype is, after all, a marketing tool to promote an idea of France and Frenchness worldwide, so it is no wonder she is associated with fashion and the luxury industry.Emmanuelle Maréchal is a very French name. Reading it, nobody could imagine that I was born in Cameroon and grew up in an interracial family. I am Black like my mother, my father is white French, and my brother is mixed-race.

Since childhood, I have always known that being French and something else was possible. In Douala, I went to a French school where pupils were predominantly Black, but there were also other children with different backgrounds. I went to school with friends who were Greek, Lebanese, Indian, and Congolese. Conversely, my parents' friends were Cameroonians, Malians, Chadians, etc. Some families looked like us; nonetheless, I wouldn’t describe Cameroon as a diversity haven. I am aware, though, that my experience is the fruit of privilege because my father was a white expat.

When I was twelve, we returned to France after five years of living in a diversity bubble in Cameroon. We were in 1999, and I couldn’t grasp why nobody, from my classmates to teachers, could reconcile that I could be both French and Cameroonian. Not only did they not understand my high grades - because an African person is obviously less intelligent than a white one - but there also was disbelief about my fluency in French and differential treatment when it was my mother who participated in school meetings instead of my father, but above all, the mockery I received about my appearance made me immediately understand that I wasn’t the norm for them. It was a real cultural shock that taught me that France in these years wasn’t able to understand that Frenchness wasn’t synonymous with whiteness. But what does a twelve-year-old non-white pre-teen do in such a context? She assimilates. In French, the verb “s’assimiler” is a word I loathe because it refers to the concept of assimilation, according to which immigrants and their children are forced to forget their roots because French culture must prevail over the colonised one as if the “mission civilisatrice” never stopped.

I never identified with the myth of the French woman or the Parisian woman. Writer and Nylon France Editor-in-Chief Alice Pfeiffer explains in her book Je ne suis pas parisienne, éloge de toutes les françaises (I am not Parisian, an ode to all French women),”[the Parisian woman] has one face, a Parisian woman invented and embodied year after year by celebrities that are the carbon copy of one another. This Parisian woman coopts fashion’s narration and reveals the absence of multiplicity in the national representation.” The Parisian woman seemed more like the girl next door when fashion democratisation happened through the internet in the 2010s. Before, she was a famous actress or a singer like Brigitte Bardot, Françoise Hardy, Marion Cotillard, or Vanessa Paradis. From the 2010s on, her name was Caroline de Maigret, a model and music producer who published in 2014 with her friends Sophie Mas, Audrey Diwan, and Anne Berest How To Be A Parisian Wherever You Are: Style and Bad Habits. On the book cover, there is the distinctive Caroline de Maigret silhouette in her rock chic uniform composed of skinny jeans, an oversized blazer, and ankle boots. A cigarette and a coffee complete the look. Caroline de Maigret is the epitome of the “cool” Parisian woman who would almost make you forget her aristocratic background if not for her patronym. Her friends, instead, don’t have a last name that gives away their belonging to a privileged social class. Still, they respectively are a film producer, a director, and a writer. So they all belong to the cinema and arts world. I remember giggling when reading the book as an ironic handbook about the “quintessentially Parisian art of being a woman,” it contains clichés aplenty.

Another figure that emerged in these years was the blogger turned entrepreneur Garance Doré, who in 2015, published her book, Love.Style.Life. Garance Doré embodies the southern French girl who goes to Paris “to make it.” Born Mariline Fiori in Corsica to an Italian father and a Moroccan mother, she has an intriguing profile in the French context as she doesn’t match the Parisian girl stereotype. She began her book by dedicating it to her Moroccan grandmother, Tahmament, who she describes as follows: “My grandmother always dressed in bold colours and prints, bright frocks that complemented her long red henna-tinted hair. She loved dressing up, but she had to work within the strict codes that were imposed on her. Don’t show a lot of skin; play humble.” About her mother instead, she wrote: “My mother is the opposite. She’s a free, modern woman and she wants the world to know. She wears tight jeans and irons her hair, and every outfit is perfectly thought out.” Her descriptions of the two women highlight the concept of assimilation culturelle (cultural assimilation): the grandmother’s style recalls the tradition shackle, whereas the mother’s is free and modern, which somewhat reminds of the Parisian woman. French society has taught entire generations of non-white people to approach their roots as something exotic. And Garance Doré, even before Jeanne Damas, is undoubtedly the French blogger/influencer who built her entire career on the Parisian/French woman concept. On the subject, French fashion journalist Mélody Thomas says, “The Parisian woman is an archetype built on marketing needs. The industry uses that figure to sell a certain myth of French fashion abroad.” And it is precisely what Garance Doré did by changing her name and talking to her international audience on her blog as a French woman in Paris first and then in the U.S.A.

The Parisian woman is a myth we all grew up with, deeply rooted in France’s DNA. The problem is that it didn’t evolve with time, but above all, it doesn’t reflect the country’s social change. Walking in Paris streets, it is clear that the Parisian woman is Black, North African, Asian, South Asian, and so on.

I was born in 1987 and grew up in Bordeaux, a very bourgeois city in southwest France. My father arrived there to study from Vendée, which at the time was quite a poor region yet boasts a rich history as the region that fought to keep Louis XVIth in power during the French Revolution. To assimilate - because assimilation also applies to social classes - my father adopted the culture and style of the Bordeaux bourgeoisie. He passed on to me very French and bourgeois values that make me a real social chameleon as they coexist with my Blackness and Africanity that my father fostered, providing information to my brother and me about the place where our mother came from. But, I quickly realised I had no model to turn to. Back then, in the glossies pages and on TV, there was no Black French woman whose story was similar to mine. My father understood it the harsh way when we returned to France. He thought he only had children, not Black and mixed-race children. Society reminded him systemic racism existed when he couldn’t gift me make-up matching my complexion or when he discovered Black mixed-race people have very sensitive skin requiring specific attention. Still, there were no products adapted to us in any shop. My father’s concerns are what has given me the confidence I have today. When I was fifteen, I decided to keep my hair natural. My mother worried about how I’d care for them without any examples. And she was somewhat right. My style icons then were Afro-Americans because there were no Black French icons.

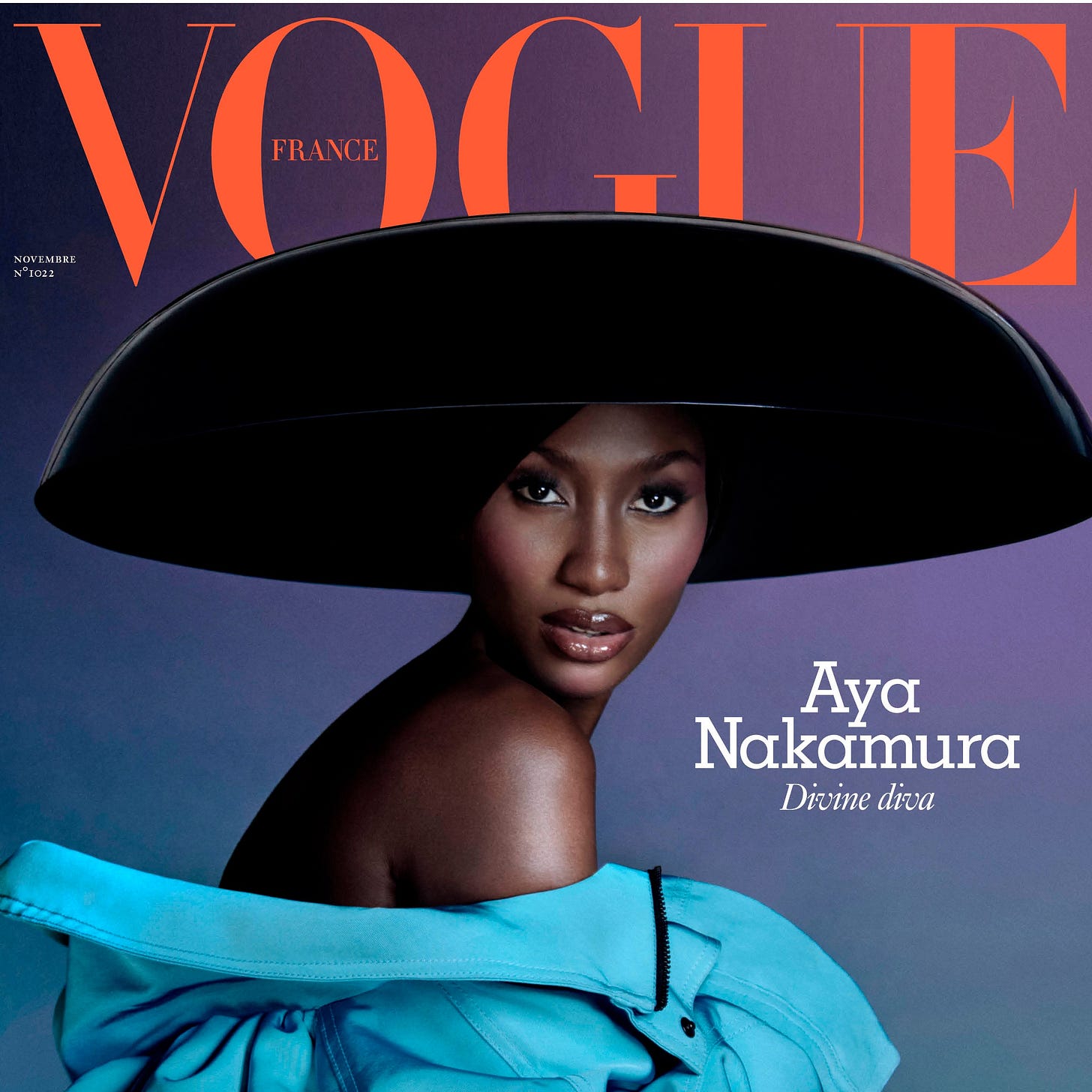

I had to wait until November 2021 to see French-Malian singer Aya Nakamura on a Vogue France cover.

On the subject, Mélody Thomas remains cautious,” the question of the archetype of the French woman that is a carbon copy of the Parisian woman beyond the rest of the country is yet to be determined. The negative reactions when Aya Nakamura became Lancôme’s ambassador are enough to prove it.” Another similar example is Vogue Italia's February 2020 cover of Italian-Senegalese model Maty Diba Fall, which provoked hostile comments. Albeit there is no equivalent marketing system that defines the Italian woman with strict rules, such reactions make understand that the ideal Italian woman is embodied by celebrities like Mina, Sophia Loren, or Monica Bellucci.

I am curious about your thoughts about that type of stories. Today’s was more focused on fashion and beauty standards, but I would like to know if you’d enjoy reading more about my family’s story. Let me know in the comments!

I was reading the comments after your interesting article and I was thinking it is funny and frankly quite sad that such a diverse species as ours insists in erasing difference as if it was a bad thing, when it ahould be embraced and celebrated. Europe in particular has a lot of growing up to do.

Regarding your article, the myth of the parisian woman is a construct that sells clothes, food, hotel nights, and something people love, an irreal aspirational ideal that is Impossible to fulfill. A while ago I saw a great video on YouTube where a group of French women who represent France's true diversity talked about the esthereotypes that reign and how they felt about them. I might have told you about it already, I'm thinking now... Anyway, as you say, it also has lots to do with promoting the fashion industry, particularly to american women. Emily in Paris, anyone??

About your writing, may I suggest whatever feels important to you? This is your space, recently I been reflecting that only thing that works is talking about what we care about so yes, if your family history is something that for you, we'll enjoy it.

Thank you for sharing your story! As someone who grew up on the French chic/ Parisian woman myth, I admit it took me a very long time to understand why it was so problematic. And I should know better! I’m Chinese and born and raised in Singapore which has Chinese, Malay and Indian people, but growing up it was always mixed-raced models who could pass as white on the magazine covers-it was as if as a country we did not consider ourselves beautiful enough and we completely erased ourselves from media, or underwent plastic surgery to confirm to white standards of beauty. Myths like the “Parisian woman” may seem harmless to outsiders like me but I know better now...

I really enjoyed and learnt a lot from your story and would love more of such pieces if you decide it’s a direction that works for you :)