So You Think You Can Be French? Aya Nakamura, The Black Parisian Woman Between Politics And Fashion

This newsletter has been in the making for a while, but the last results of the European elections and Vogue World Paris shook everything, at least for me. We often think fashion and politics are separated, yet they marry for better or for worse.

In France, the European elections saw the rise of the far-right party Rassemblement National (National Rally)—the former Front National (National Front) founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972. Adding to the climate of uncertainty with the general elections approaching, Emmanuel Macron dissolved the Parliament. The last time it happened was 27 years ago when Jacques Chirac was president. When a French head of state decides to dissolve the Parliament, it usually means he wants to end a crisis. And it is allegedly what Macron wanted to avoid. A crisis.

To explain further why he chose to dissolve the Parliament the French president wrote in a letter to citizens on June 23rd, “The way our Parliament operated and the disorder of recent months could not continue any longer. The opposition was preparing to overthrow the government in autumn, which would have plunged our country into a crisis at the very moment of the budget plan[…]So yes, this dissolution was the only possible choice to acknowledge your vote in the European elections, to address the current disorder and the greater disorder to come, and to act at a time when our country is facing historic challenges.”

The French parliamentary elections were bound to happen this summer anyway, yet by choosing to dissolve the Parliament, Macron accelerated the process and maybe put the country at risk of having a far-right Prime Minister in the person of Jordan Bardella. The 28-year-old Rassemblement National president, who happens to have an Italian father and an Algerian great-grandfather1, has in the program with his party to:

prevent citizens with dual citizenship from working for governmental entities pertaining to the defence and security of the country;

abolish the jus soli or right of soil

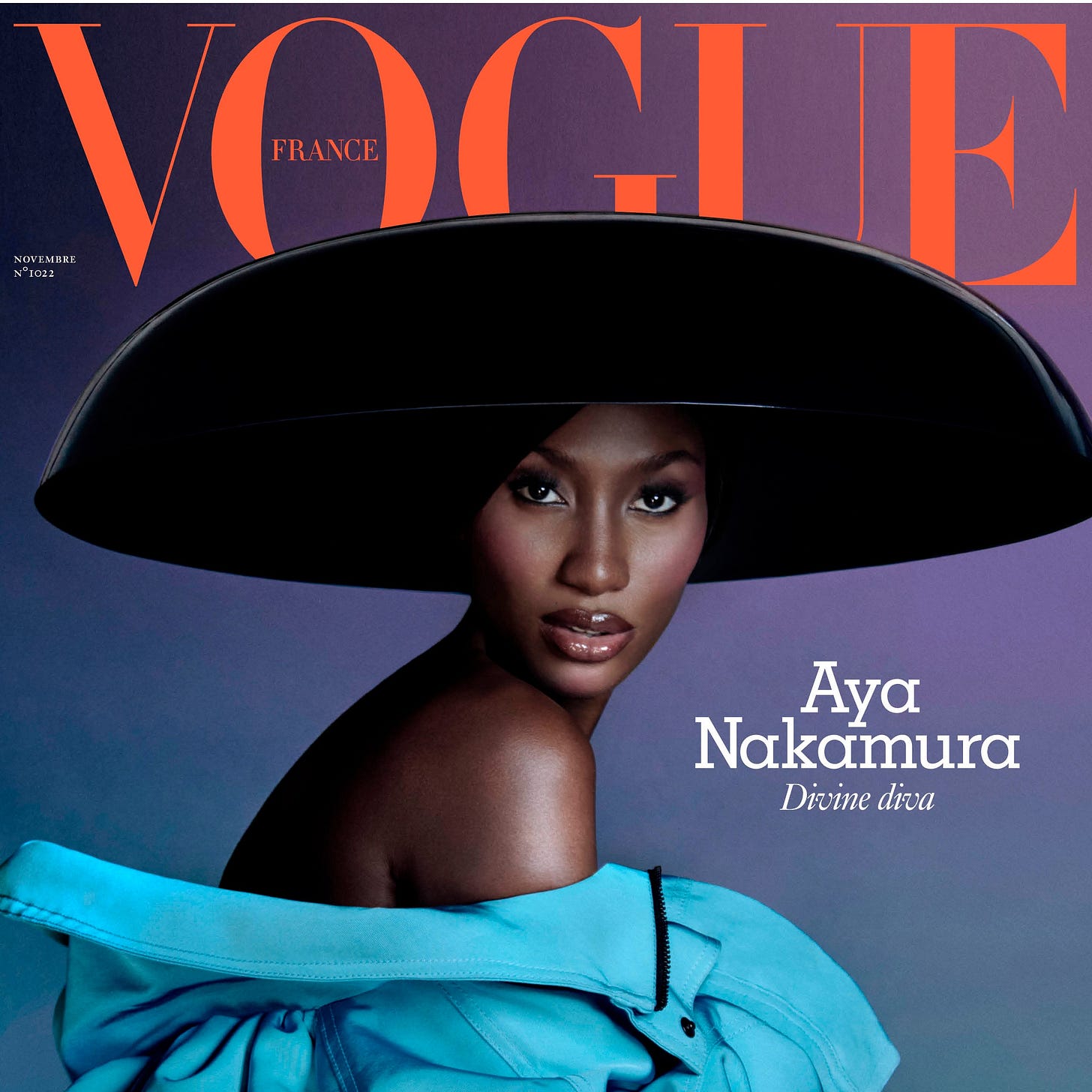

The same day Emmanuel Macron sent his letter, the French-Malian singer Aya Nakamura sang in a chocolate brown Jean-Paul Gaultier dress adorned with raffia fringes. A steep transition from politics to frills—or not. The 29-year-old artist, who since Edith Piaf is the most-listened-to French-speaking female artist worldwide, was also the first Black French woman to grace the cover of Vogue France in 2021.

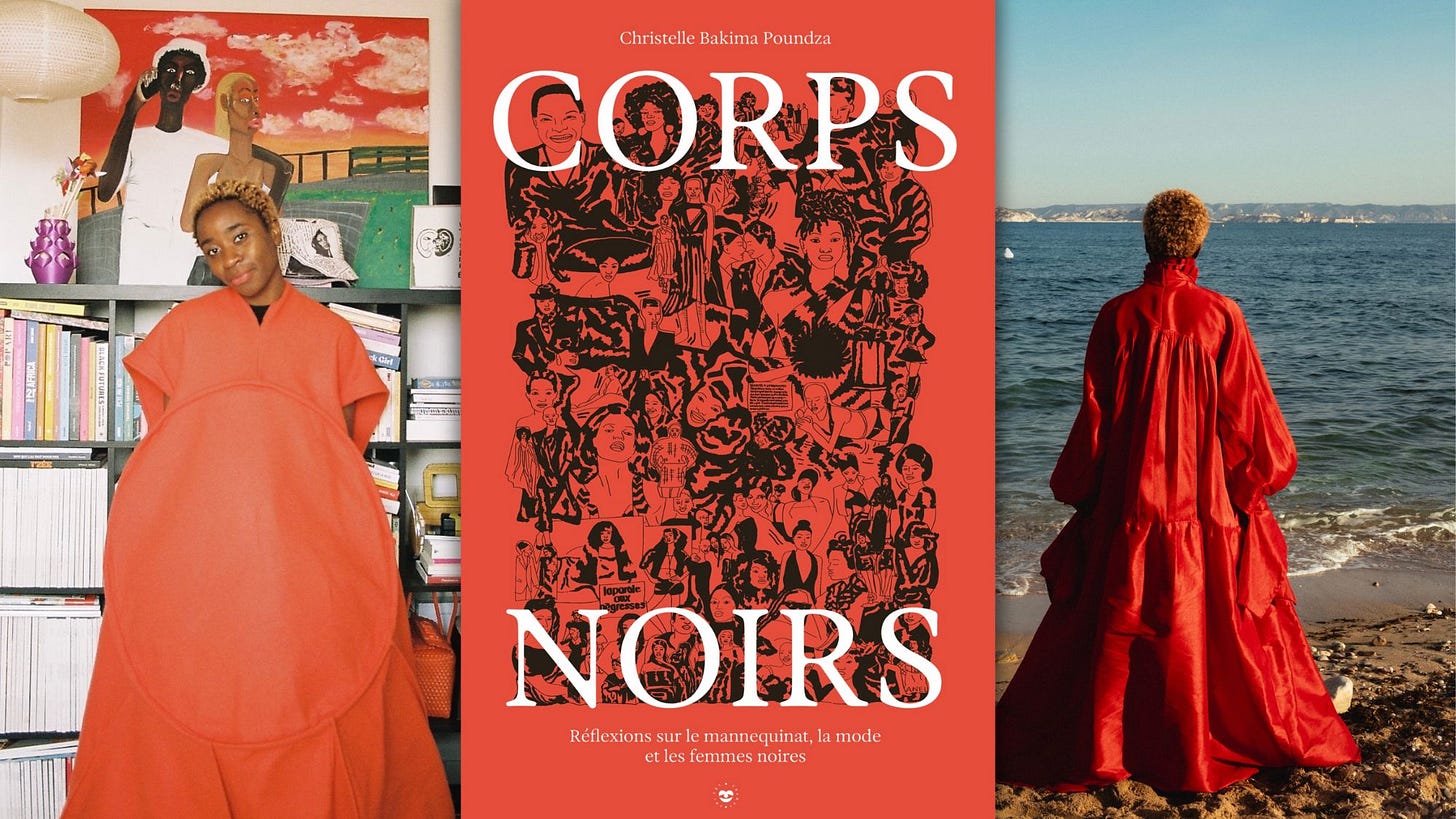

About that cover, French-Congolese author Christelle Bakima Poundza writes in her book Corps Noirs, Réflexions sur le mannequinat, la mode et les femmes Noires (Black Bodies, Thoughts on Modelling, Fashion, and Black Women):

Curiously, by choosing Aya, it seems the magazine is justifying itself. For the occasion, they developed a narration around the notion of identity and revival, as if the artist couldn’t have been chosen for what she is [….] I must say I felt ill at ease with the exploited timing and narration. It made me feel that, again, they used a Black woman to convey a message that isn’t hers.

Christelle Bakima Poundza cleverly notes that Aya Nakamura was the perfect cover girl for the Condé Nast French glossy as she graced their first edition after they rebranded from Vogue Paris to Vogue France. That’s the timing she is referring to in the quote above. As she rightly adds, “The cover is remarkable because it is something that has never been done in the past: put on the cover of Vogue Paris/France, a woman with a working-class and African background, proudly banlieusarde2, and with firm Afro-French influences. It is totally unprecedented.”

On top of her musical and fashion success, Aya Nakamura has become the first French Black ambassador to the storied beauty brand Lancôme, along with women like Julia Roberts and Zendaya. Therefore, in French society, she has a lot of firsts, or better said, is the first. Rightly, for that reason, she has been a constant topic of discussion, dissent, and, unsurprisingly, the subject of racist threats and attacks. She is the most controversial and political French figure for just being what she is. A Black French woman.

Case in point, when a rumour started that Emmanuel Macron considered her to open the Olympic Games in Paris, the internet, the media, and everyone and their mother went berserk on a woman who clearly just wants to sing. In an interview in Marie-Claire France by journalist Christelle Murhula in 2021, quoted in Christelle Bakima Poundza’s book, she said:

“I am Aya. I was born 24 years ago in Bamako. I grew up in the 933, and I am nor a caricature nor an example. Just a girl who says thank you, thank you to life. I just want to be myself.”

This quote is one of the many similar ones she gave to her interviewers throughout the years, and it echoes exactly what author Christelle Bakima Poundza wants to highlight: Aya Nakamura doesn’t have the privilege of just being an artist. She needs to represent something, whether for her supporters or critics.

Seeing Aya Nakamura, an unapologetic banlieusarde, entering Place Vendôme, the home of the finest jewellery French maisons, accompanied by an orchestra, will still mark generations of Black French girls to come. But not only. In a context where France struggles to understand that its identity is multiple, her entrance into Place Vendôme, a space embodying the epitome of that white Frenchness marketed abroad via the Parisienne, looks surreal. It is almost utopian or, dare I say, dystopian. And in a sense, it is, because as the ‘first of,’ Aya Nakamura singing on Place Vendôme feels like a tale meanwhile, outside of the Vogue glamorous ramparts, France is literally on the verge of imploding.

I had to stop when Jean-Paul Gautier described Aya as the perfect silhouette because have you ever heard a French designer talk about a Black French woman that way? The mention of her proportions is interesting to notice because it shows that fashion can adapt to different types of bodies. I also appreciated that when asked THE big question, aka what France she represents (if she were Marie Dupont, she wouldn’t be asked such a thing), he didn’t dwell on it and instead chose to highlight her personality traits. I thought this video was worth sharing because, besides THE big question, Jean-Paul Gautier is talking about her as the model wearing his creations AND a woman whom he sees as beautiful inside out. And it is important to say as she is subjected to virulent misogynoir.

Outside of Vogue castle, Aya Nakamura, born in Mali in 1995 and who only obtained her French citizenship in 2021, is continuously told she doesn’t and can’t embody France by the internet and politicians - exactly like millions of Black and Brown French people who are under the spotlight. One thing that reminds me of that is a picture of her in her Vogue France interview. In it, she is wearing a football jersey with the writing France on it. The image seemed to reference the 1998 football World Cup that France won with a team coined ‘Black, Blanc, Beur’ - Black, White, Butter (the last term was used to describe North Africans, note how France doesn’t see colours, and yet…) - because the football players represented France's multiculturalism under the condition/injunction for Black and North African players only to love France forever and ever. Meanwhile, their Caucasian counterparts didn’t have that obligation.

I felt that the football jersey showed that Vogue France was still stuck in 1998. Above all, it subtly told through images that Aya Nakamura still needed to prove she was French. There you have the message that Christelle Bakima Poundza was talking about.

As Vogue World decided for this edition to call Paris home, the theme chosen was the Olympics, the same event that is causing social and economic turmoil in the country, such as heightened police checks, prices spike, migrants pushed back further and further outside of the city with no policy in place to relocate them, and evictions of people living under the minimal wage. All this is for the City of Lights to look like a shiny paradise of tourism and consumerism. In a certain fashion podcast, an American journalist lamented people complained about the event, stating it fulfilled its function of making money and entertaining (rich) people. While I understand her point, I wanted to tell her just one thing: “context!”

Aya Nakamura, whether we like it not or not, is a fascinating figure to analyse because she embodies this invisibilised Parisian woman of the outskirts. She is also fascinating because whenever there is a (non) polemic around her, like her being a Lancôme ambassador or singing at the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games, politicians from all fronts talk about her when she doesn’t say or do anything political. And she is a singer. An entertainer. Unlike many Black and Brown French artists, she is not vocal about her political stance, yet she has become a politicised figure that politicians use to gauge Frenchness. When people comment she has no elegance, doesn’t know how to speak French, looks manly, etc. They think they are talking about the Parisienne/French woman, but really, they echo that fashion in France is part of the res publica (public affair).

Jordan Bardella is part of these French political and public figures and French people whose family immigrated from Southern and Easteen Europe, North Africa, and Africa who are the most radical about Frenchness and immigration. They are the perfect embodiement of assimilation.

A banlieusard is someone living in a banlieue. France is very centralised and it shows in the cities’ architecture. The closer you are to the city center, the wealthier you are, the farthest you are from it the poorer and excluded you are. And Aya Nakamura is from the latter.

93 refers to Seine Saint-Denis a department, but also one of the metropolis making the Grand Paris.

Love this piece...I wouldn't have even given Vogue World a second thought if not for Aya Nakamura, and it's very clever of them to bring her into the fold because she matters more in the greater cultural scheme of things -- I actually don't even know her songs but I have heard of her because the stir she creates in France is global news. Your piece really gives the context for understanding why the way Vogue has capitalised on her cultural relevance is troubling, even if they perhaps they didn't intend it cynically (after all, she is absolutely deserving of the stage she was given).

As always this is absolutely brilliant. It made me think, and echoed parts I had thought too about how Aya was “represented” by Vogue- in that she was written about completely differently to a white woman, let alone a white man ooh la La La La 😱 I believe your Substack to be one of the most informative and powerful writings out there today. Bravo, magnifique 👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏